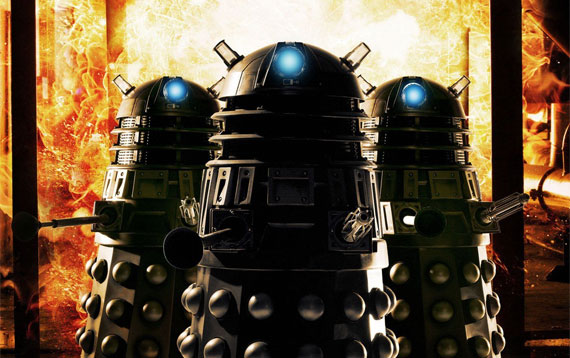

The Case For… Daleks In Manhattan / Evolution of The Daleks

Guest contributor James Blanchard defends the heavily criticised Series 3 episode.

My biggest criticism of this story is why Spiderman couldn’t save New York. That’s his job, it isn’t it?

All seriousness aside, this Series 3, two-part story is often on the end of some harsh criticism

(Daleks In Manhattan especially). In despite of this, this ingeniously devised, beautifully thought out and magnificently executed masterpiece of an episode(s) earns its well-deserved spot of my favourite New Who Dalek story.

“It’s the depression sweety; your heart might break but the show goes on.”

This wonderful piece of dialogue perfectly encapsulates the tone of Daleks In Manhattan. The Doctor and Martha find themselves thrown into a world of desperation and poverty, where idealism has become quaint and ineffectual, and you do whatever you can to get by. Hooverville epitomised the horrors of the Great Depression, showcasing how desperation can turn men against each other and those even in the highest of positions can find themselves in the same boat as everyone else. However, there was always hope (a word I intend to use a lot in this article.) Solomon (not to be confused with the villain from Dinosaurs on a Spaceship) offered a much needed sense of purpose, leadership and brotherhood to Hooverville, whilst Tullulah went out on stage every day, hoping her beloved Lazlo would return. The 1930s New York setting is utilised beautifully: it’s not fetishized to point where it dominates the entire story, but the depressing subtleties seep into every aspect. For instance, Tullulah’s stage performance makes for a wonderful expression of the seedy, exploitative nature that surrounded the era.

But these themes aren’t merely restricted to the humans making their way in the streets of New York. Underneath, the Daleks are also living by the philosophy of ‘Do what you can to get by’. After their defeat in Doomsday, The Cult of Skaro is back, doing what they were built to do: imagining new ways of prolonging the Dalek race. Here we see the Daleks at their most desperate, creating a beautiful parallel with the unfortunate humans. They sit underneath New York’s biggest symbol of decadence and ignorance, manipulating the Empire State Building to achieve their own ends. Their human puppet (in more than one sense) Mr Diagoras offered an insight into how Machiavellian, almost Dalek ideas, often thrive inside hard times. The scene where Dalek Caan speaks to Diagoras, whilst looking over the shimmering, grim façade of New York, has often engendered criticism for not being very ‘Dalek like’. Caan’s attitude is often misinterpreted as sadness, a concept which I don’t think Daleks are total strangers to (Dalek, anyone?). However, I would argue that the real emotion Caan felt here was contempt. Contempt for the human race and their productivity. How could the humans be so weak, unfocused and unambitious, but still outlive the pinnacle of perfection that is Dalek society? The answer is, of course, hope. The Daleks have no sense of hope, or that things will always get worse before they get better. They focus only on expanding, conquering, and winning. Without that hope, the Daleks are always doomed to failure.

The best way to understand the opposing ideals running through the story to look at the characters themselves. On the one hand, there’s Solomon, Frank, Tullulah and Lazlo: these are forward thinkers, hard done by, but never allowing the past to hold them for fearing of drowning under it. Frank is all about going ahead, and doing what has to be done to make things better, Solomon is about trying to get the best out of the people around him, Tullulah is about waiting, getting your head down all in the hope it’ll get better soon, and Lazlo is about trying to make the best of a bad situation. Conversely, there is the Cult of Skaro and Mr Diagoras. The sub-members of the Cult represent conservatism, trying to maintain the status quo and ensuring they always remain on top, whilst Diagoras shows doing absolutely anything, climbing over your friends to stand in the sun. Of course, the Daleks do have an exception: Dalek Sec. Sec is a highly interesting individual, one who highlights the fundamental flaw in the Dalek way of thinking, that survival and purity are not wholly compatible. “No, Dalek Thay. Our purity has brought us to extinction!” This statement rings true for much of Doctor Who. Every single time the Daleks have tried to establish themselves as superior, every time they wheel out a new super weapon or try to steal one, they always fail. Because the Daleks lack the flexible psyche that any intelligent species always needs to thrive.

Dalek Sec is a catalyst for an incredibly interesting insight to the Dalek mind frame. The Cults betrayal of their leader wasn’t exactly the most surprising of curveballs, but that said, anything less would not have worked. Once the Dalek-Purists assume control, you can feel how much they’re enjoying themselves. They love it! Barking orders with the militaristic might which they’d so missed, you really get the sense this is what the Daleks are about. “From this island, we will conquer the world!” That one line sums up the ultimate Dalek motivation: To destroy, to conquer. With this they show how much they value their purity, and their Dalek ‘social-stigma’. The idea of the Daleks’ supreme power is best shown during the scene when they attack Hooverville. Here they show off their brute force, and overriding desire to establish themselves as superior, even going as far to describe the “urge to kill” which so dominates the Dalek personality. But, inevitably, they fail. The Doctor mixes in Timelord DNA with the human/Dalek hybrids, giving them that all important psychological flexibility, that all important hope, that a species needs to thrive, causing them to turn on their creators. As Dalek Sec said, “If you choose death and destruction, then death and destruction will choose you!” How true that was. Of course Caan kills them all straight afterwards. As if the Daleks would accept defeat.

“You will identify!” “I. Am. A. Dalek.”

If Daleks In Manhattan was defined by desperation, then Evolution of The Daleks is defined by power, and how it corrupts. The story has some obvious Nazi symbolism: the 1930s was the decade when the Nazis steamrolled into power in Germany. Here we get the real sense of how the renegade Cult’s militaristic, expansionist ideas flourish in times of hardship. More parallels can be drawn from the Daleks experimentation, remaining eerily similar to experiments performed on Jewish prisoners in Nazi concentration camps, and maintaining the Dalek ethos that they are superior to all. The Daleks had ‘The Final Experiment’, an attempt to ensure the recapture their superiority; the Nazis had ‘The Final Solution’, an attempt to ensure their superiority is never toppled. Thematically, this makes for a very insightful story.

The recurring characters (i.e. The Doctor and Martha) grow excellently. “They used to be like Lazlo. They were people. And I killed them.” Here Martha learns that sometimes the moral high ground must be sacrificed in order to survive. Before now, she hadn’t truly faced any situation where her morality was questioned; however this story pushed her to the absolute limit. The Doctor, too, goes through some very interesting changes. Dalek Sec allows him to see that the Daleks aren’t so straightforward in their thinking, and can change for the better. He even offers to ‘help’ Caan. What’s more, none of the story takes place in the TARDIS. This lack of a safe haven makes for a frightening and intense narrative.

Moving away from characters and themes, let’s look at the structure of the episode. Not a moment is wasted; the Daleks are revealed within the first ten minutes and the mystery surrounding them isn’t laboured one bit. The RTD era Daleks really come into their own here, with the gold colour scheme complementing the mute, depressing tones of setting, and much of the screen presence they command is thanks to Murray Gold’s frankly orgasmic score. James Strong pulls an absolute blinder, because every shot feels perfectly placed to emphasise the scene, making for one of my favourite New Who directions.

The story isn’t perfect, of course. Dalek Sec’s prosthetics would have benefitted much from a more subtle approach, and so could Eric Loren’s performance, for that matter. The Daleks seem to able to pull some of their technology (Dalek tommy guns, for instance) out of the big book of plot conveniences, and Helen Raynor appears to have done all her research on genetics out of a primary school text book. But even with these nit-picks, I thoroughly enjoy this excellent piece of entertainment.

To conclude, then, Daleks In Manhattan and Evolution of The Daleks are two brilliant, but underestimated stories, rife with symbolism and executed wonderfully, creating, in my controversial opinion, a true, modern, Doctor Who masterpiece.