Clara Oswald: A Study of the Impossible Mirror

Guest contributor Ruth Long continues her tribute series looking back over Jenna Coleman’s companion.

As we close her final act, I wanted to pay tribute to the companion that has defined and driven my experience as a fan of the show. ‘A Study of the Impossible’ is a series of articles examining the character of Clara Oswald. In each chapter, we will be exploring the Impossible Girl in her journey with the Doctor: from the moment she set foot in the TARDIS, to the day she bade us farewell. This second part will predominantly focus on Series 8, though naturally, there will be references made to her entire tenure.

In the first chapter of this series, we discussed what I (and other fans) see as Clara’s personal need to be “better, and more, than she really is”; a concept that I believe was well established in her debut run on the show. I also highlighted several noteworthy aspects of her character (in Red) that I promised we would return to: so as to measure her progression. There is, however, a particular theme associated with the Impossible Girl that demands a significant degree of our attention; one that, especially under closer scrutiny, is arguably one of the most complex, compelling and fascinating journeys that a companion has ever embarked on.

Since the show returned a decade ago it has toyed with an idea: What if the companion, in their travels through space and time, began to reflect the Doctor? Such a question has been addressed in various different ways with each companion of the revival. Generally this is evidenced in the respective character’s maturation and development; on other occasions though, it’s much more overt. Such as Rory’s indignant “It’s not fair, you’re turning me into you” in ‘The Girl Who Waited’, Martha’s dilemma to end Earth’s suffering in ‘Journey’s End’, Davros’ declaration on the Doctor’s “children of time” in the same episode, and indeed, Donna quite literally becoming part Doctor.

Of all the pre-Clara companions however, it is Rose that provides the best answer. Aside from her post-departure appearances that do see her in a Doctor-like role, my thoughts pertain to one scene specifically. In the episode ‘Army of Ghosts’ there is a conversation that takes place between Rose and her mum. It’s a short exchange, which nevertheless is an eminently telling, near-prophetical statement on her daughter looking more and more “like him”. Though despite Jackie’s assertion that she’ll “keep on changing”, it’s not Rose who would ultimately fulfill those words (thanks to the events of ‘Doomsday’); that part remains for Clara to play.

“And in forty years time, fifty, there’ll be this woman, this strange woman; walking in the marketplace on some planet a billion miles from earth. But she’s not Rose Tyler, not any more. She’s not even human.”

As Steven Moffat explained in the above quote, Clara’s symmetry with the Doctor dates back to her very first appearance(s) on Doctor Who. Oswin’s description of herself, “Is there a word for total screaming genius that sounds modest and a tiny bit sexy?” is met with “They call me the Doctor”. Then there’s Victorian Clara’s fast-talking, quick-witted rapport with the Time Lord (“No I do the hand grabbing, that’s my job that’s always me!”). Even Clara prime, through her story arc, subverts expectations by assuming the mystery element typically reserved for the Doctor: forcing him into the ‘audience-surrogate’ position usually occupied by the companion

(The prequel ‘She said, he said’ is a great example of this – they are both pondering the other’s true nature in similarly shot and written scenes).

Most importantly, Clara is predisposed to be Doctor-like, more so perhaps than any of her predecessors. An unconventional young woman who’s enamored with the prospect of travel and adventure (“Joined the Alaska to see the universe”, “Ideas above her station”, “101 places to see”); she’s very smart, very brave, very kind and definitely not lacking in self-confidence, which can occasionally border on arrogance. However, assurance in herself and personal insecurity are not mutually exclusive; in fact, as we learned in the previous article, the latter informs the former. Clara hides her fear and uncertainty, which in turn is what drives her. Now, who else does that remind you of?

It may have existed in the subtext, but it’s in Series 8 that the parallels between the two characters really begin to come to the fore, and believe me when I say that they are extensive. They can be as simple as repeated phrases (you’d be surprised at how much both say “a thing” and “shut up”), some of which are associated exclusively with the Doctor (“You’ve redecorated; I don’t like it”), or as complex as shared themes, qualities or recurring metaphors. The evolution of Clara’s character across the episodes sees her progressively resembling her best friend more and more: whether either is really aware of it, she is in many ways a ‘Doctor in training’.

Up until ‘Deep Breath’ Clara had it fairly easy where her relationship with the Doctor was concerned. The floppy haired, bowtie-wearing ‘young’ man, ancient and wise though he was, happily obliged to letting her stay in her element: comfortably and completely in control. But in the blink of a fierce-browed eye that all changes; his veil lifts, and thus so does hers. Challenged by her best friend’s new and unpredictable persona, it is here that the carefully maintained pretence of Clara Oswald begins to slip in earnest: revealing the “bossy control freak” underneath. What this has the additional effect of doing is creating further opportunities to insert a mirror between the two characters, with fascinating results.

In their first proper scene opposite each other: the argument in Mancini’s Family Restaurant, the Twelfth Doctor and Clara manage to have an amusing but revealing misunderstanding over who placed the ‘Impossible Girl’ ad. Each believes that the description of “egomaniac needy game-player” refers aptly to the other, though ultimately they both end up highlighting aspects of themselves (they are also inadvertently identifying their own similarities to Missy – but that’s a discussion for another day). This sets a precedent that will be recurrent throughout the rest of Clara’s time on the show. Indeed, in many ways, the character’s trajectory this series is an unfolding tale of ‘the police-box calls the TARDIS blue’.

The first half of Series 8 concentrates on Clara’s desperate attempt to sustain two separate lives; a feat she previously managed to achieve with relative ease until an angry Scotsman barreled into her life. It is of course a natural expression of her need to maintain control and keep up appearances – whatever the cost. This struggle is personified in the form of Danny Pink: Samuel Anderson once described his role as “the companion to the companion”, and it’s a remarkably accurate summation of Danny’s narrative purpose in relation to Clara’s arc. He serves as ballast for her in very much the same way that she grounds the Doctor.

Furthermore, on a metaphorical level, Danny is a physical representation of Clara’s ties to earthly normality and her increasing disparity with it. As her realities begin to clash with rising intensity, the wall between them crumbles: culminating in the hall scene in ‘The Caretaker’. Here, Danny’s immediate assumption is that like the Doctor, Clara is an alien (“You’re a space woman, you said you were from Blackpool”). A reasonable conclusion to jump to given the circumstances, but one that also sheds light on just how a companion (especially this one) is perceived against the background of the ordinary. Eventually, they can appear as otherworldly as the Time Lord they accompany.

As the episode ends, Danny reflects on Clara’s behaviour, likening it to his own experiences as a soldier: “I saw you tonight, you did exactly what he told you. You weren’t even scared… and you should have been”. Already we’re beginning to see an indication of her becoming desensitized to danger. This isn’t the brave face of Series 7 worn in spite of fear, but the hardening fortitude of Clara herself. She has been conditioned by her adventures with the Doctor: pushed, made stronger, learning to “do what has to be done” until she’s accomplishing things she never thought she could.

But it’s time for the stabilizers to come off. ‘Kill the Moon’ is an astronomical character turning point in a way that it’s not often given credit for. The central plot is an education for Clara as she’s thrown in at the deep end; forced into the Doctor’s position without the help or guidance of the man she trusted. Perhaps the most important observation to be made from this story is the way in which it challenges Clara’s understanding of the Doctor, when he contradicts a philosophy that she holds at her core: “We don’t walk away”. Clara never runs out on the people she cares about, but she watches, incredulous, as he does just that.

The confrontation that ensues is as significant as it is tempestuous. The Doctor opines that his actions were a mark of respect for Clara (and the human race): demonstrating the level of his confidence in her abilities (“I had faith that you would always make the right choice”). From Clara’s perspective however, it was a callous and patronizing betrayal. When he was faced with a button and a terrible decision, she didn’t abandon him; she didn’t declare that Galifrey wasn’t her planet, that it wasn’t her business to interfere. She didn’t turn her back when he needed her most.

Clara’s remark on the Doctor’s condescension tells us far more about her than it does him. With her words she defines Clara Oswald as something more, something different from “all the rest of the little humans” that are so “tiny and silly and predictable”. In that moment, Clara sets herself ‘apart’ from other people; outraged to be “lumped in” with them in his eyes. A spotlight on her egocentricity, but even more crucially, a statement on what Clara wants to be. This is a woman who will ignore the will of her entire planet to do what she feels is right.

As the hurt dissipates, there arises a growing appreciation of a dangerous addiction. Despite her accusations and her anger, Clara quickly allows herself to become swept up in a new mystery on the Orient Express: its allure eclipsing any notion of a quiet “last hurrah”. “I thought you didn’t want to do this any more,” says the Doctor, and therein we see a glimmer of her hypocrisy. She reprimands him for making her an accomplice; yet lies to Maisie of her own volition. She’s disgusted at his misleading; yet creates her own tangle of dishonesty. It’s scary, it’s difficult, but she’s learning to love being the woman making the impossible choice – even if she won’t admit it.

If Clara Oswald is defined by the stories she tells, then her story is changing. ‘Flatline’ reveals where she wants to lead her narrative: The mantle of ‘the woman born to save the Doctor’ has been exchanged for that of her own impossible hero (“Once the stories started, she could hardly stop herself. You are her hero, I think”). In many respects it’s an examination of Clara’s abilities; a test of her resolve and the lessons she has learned thus far as the Magician’s apprentice. She’s ready to embody the Doctor’s approach and all that comes with it, and in doing so embraces a side of herself that she once endeavoured to conceal.

We’ve seen Clara thrive in positions of leadership and responsibility before; however, here it takes on a whole new meaning. It’s an undeniable contrast to the plucky nanny placed at the head of a punishment platoon: there’s no overzealous bossiness to the proceedings, instead the resolute command of a mysterious, pragmatic adventurer on whose shoulders alone rest everyone’s survival. Clara employs the necessary “professional detachment” for which she so apologetically made excuses previously (“Forget Stan. Your friend’s gone”). She motivates not with reassurance or emotional appeal (her hallmark of times past) but cold logic (“You’re not getting off that lightly; there’s work that needs doing”). She’s quick to turn to lying and measures death “on balance” – a far cry from the disconcerted young lady for whom it “all got very real”.

The distance carved between Clara and ‘normality’ continues to expand; no longer does she easily fit into that world, or even really belong to it. Despite the Doctor’s warnings she quickly manages to perturb Rigsy with her eccentric behavior (“How would I scare him off?”). Note that he (like Danny) also initially presumes that both of them are aliens, and Clara’s certainly not helping that impression (“Leave her – she’s lost it”). With this comes a striking change in priorities. When facing a world taken over by the forest, her thoughts are occupied by the thrill and intrigue of the situation; not the students in her care (“The question is, how did it get here?” “No. The question is how are we gonna get these kids home?”).

It’s a remarkable departure for a character who has traditionally been strongly associated with looking after and inspiring children, emphasized in episodes as recent as ‘Listen’ or ‘The Caretaker’. We have reached a point at which her inherent fascination with the wonders of the universe is starting to surpass her ability to connect with those around her in the way that she used to. “Do you know what I hate about the obvious? Missing it!” Clara’s attempt to climb a fence with a gate right next to it echoes the three Doctors’ convoluted plan to open their unlocked cell door in ‘The Day of the Doctor’ – Her outlook is now much more akin to a madwoman in a box than an English teacher from Lancashire.

It’s her parent’s romantic fairytale: the one that paints Clara Oswald’s beginning. A love story that inspires her own; imbuing her past with magic and bringing infinite meaning to a fallen leaf. A man, a woman, a road and a car. But a life saved is now a life shattered. Danny’s death has none of the drama or scale of a grand epic: it’s a simple everyday tragedy, and that’s not good enough. “He was alive, and he was dead, and it was nothing.” Clara’s outgrown the sentiment of soufflés and the innocence of fairytales; she demands a story that justifies the depth of her grief, and so writes one worthy of it.

She’s lost once again: surrounded by orange smoke and flickering fires. The leaf that brought her home from the wilderness of the Doctor’s timestream has been replaced with a TARDIS key bound for destruction. This time she’s not defying an ancient God but the closest person to her in the whole universe. The line between virtues and flaws becomes blurred as her willingness to do and sacrifice anything to save the ones she loves is twisted into betrayal. Clara’s strengths are so often her greatest weaknesses; her love and loyalty pushed into desperate ruthlessness. Yet another thing the Doctor and her have in common.

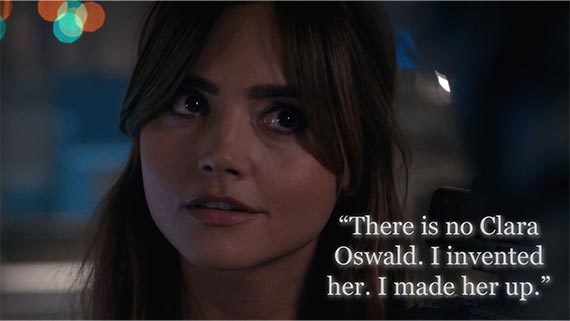

Clara Oswald is a creation of her own design: a cover story, a disguise, a mask that takes many forms. But the façade one chooses to wear is often a self-portrait. It’s no co-incidence that she impersonates the Doctor when deceiving the Cybermen; after all, who better to copy than the man she’s already so alike? Even out of context her ploy captures an essence of her character: fiction, make-believe, composing her life into the pages of a book (“Stories, stories, stories – I made them up. Look, ask anyone who knows me, I am an incredible liar”).

Still, the charade cannot last forever. In the ashes of a volcano we find someone who’s broken and imperfect and dangerous and afraid. The constant battle for control briefly collapses under the weight of Clara’s own anguish and desperation; exposing everything she tries so hard to hide. In its wake leaves the unforeseeable: forgiveness, after all she’s done. The Doctor accepts her in a way that she never could, for him, “Just Clara” will always be enough. Because that’s the crux of this relationship: The tug of war of ‘do as you are tolds’ pales alongside an unconditional love and understanding that whispers through a lonely barn on Galifrey and weaves itself between the words “do you think I care for you so little that betraying me would make a difference?”

The second act concludes fittingly; with a parting of the ways founded on common lies. Two brilliant, dysfunctional individuals who think they know best giving up everything for the other. Of course they’d say goodbye with a hug: the impossible mirror of two unseen faces that say everything unsaid. “Thank you for making me feel special” seems an awfully restrained understatement after all that the Doctor and Clara have been through, but one that describes them perfectly. As the TARDIS dematerializes it leaves behind this woman, this strange woman; walking in the street on some planet called Earth. She’s Clara Oswald, who doesn’t want to be the last of her kind, but in many ways, she’s the only one.

Apologies for the length of this article (and its lateness); there was so much to cover! Once again I’d like to thank Caitlin for her inspiration and excellent pieces on Clara; you can check out her blog here. Likewise see ‘Till the Next Time Doctor’ here for their fascinating interpretations on the character.

I hope you enjoyed this article! What are your thoughts on Clara in Series 8? And how do you view the parallels between her and the Doctor?