Heaven Sent Review (Part 1)

Clint Hassell gives his verdict on the eleventh episode of Series 9.

A really great episode in a notably uneven series, “Heaven Sent” owes a large part of its grandeur to Steven Moffat’s script. Though it doesn’t match his series-redefining “Listen,” “Heaven Sent” certainly ranks alongside Moffat’s Davies-era scripts and “The Day of the Doctor” as a modern classic.

Remarkably, Moffat turns the episode’s most obvious drawback – – with Clara absent, there is seemingly no reason for the Doctor to provide the exposition necessary for plot advancement – – into its greatest strength. Truly, “Heaven Sent” could not have aired at any other point in Series 9, as Moffat keenly uses the Doctor’s anger at Clara’s demise as opportunity for the Doctor to become boastful and verbose toward his unseen captors. As the episode progresses, the isolated Doctor continues speaking to his former companion, seemingly out of habit, perhaps out of denial. By providing thoughtful reasons for the Doctor to continue speaking aloud, the audience is given the chance to see a Doctor uncharacteristically unhinged and unmasked.

Despite depicting a Doctor trapped in an eternal prison designed especially for him, “Heaven Sent” manages to be quite funny, especially in the first act, where an exasperated Doctor dryly remarks, “I’ve finally run out of corridor. There’s a life summed up!” Moffat uses these moments to levity to slyly remind the audience of the Doctor’s character, before slowly peeling back the layers of his persona to examine what makes the Time Lord tick. The Doctor’s revelation that he “hate[s] gardening” because “it’s dictatorship for inadequates, or, to put it another way, ‘it’s dictatorship,’” is eminently quotable, yet elucidates that Twelve both loathes and reviles oppression, ostensibly an important point as the Doctor faces the Time Lords.

In dissecting Twelve, “Heaven Sent” borrows from Inception, creating a reality-within-a-reality, inside the Doctor’s mind. In times of peril, stress, and uncertainty, the Doctor retreats to this TARDIS-shaped safe haven, where he reasons out his plan of action by way of showing off to Clara. Note, however, that the Doctor is not yet able to look at Clara’s face; the memory is too fresh, even 7,000 years later. While Doctor Who has long demonstrated the titular Time Lord to be brilliant beyond measure, it has never examined the inner workings of the Doctor’s mind in such a concrete manner.

The symbolism tying the labyrinthine TARDIS to the Doctor’s most personal thought processes is especially apparent when Twelve jumps out of a castle window and into the sea below. As the Doctor blacks out, so do the TARDIS’ interior lights, leaving the viewer literally in the dark about the Doctor’s well-being. As the Doctor awakens, the TARDIS regains power. The effect is illuminating, further demonstrating the Doctor’s deep connection to the TARDIS. The concept is so well established that the episode is able to demonstrate the Doctor’s weakened state, using the newly-introduced symbol, in the third act.

“Heaven Sent” is rife with other effective symbols. Perhaps the most effective occurs in the teaser, as the Doctor’s narration describes how, throughout life, death creeps ever closer; that, eventually, one will find a second shadow next to their own, and then they will die. Not only do these words encourage an active, rather than a sedentary or complacent, life – – paralleling Clara’s story arc – – but the accompanying visual of hands restarting the teleportation machine show the audience, in typical, obscure Moffat style, exactly how the episode will play out, without actually flashing forward to the denouement. The twist is that the two shadows are both the Doctor’s; the hands seen at the start of the teaser are the hands of the previous copy of the Doctor who burned up creating the iteration of Twelve that “Heaven Sent” first follows. Forget “two shadows,” this is foreshadowing!

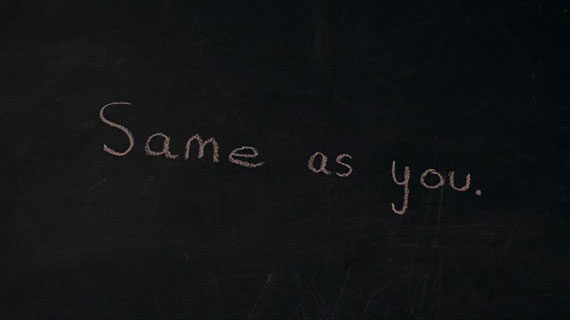

The chalkboard motif – – first seen in “Listen,” and used in “Last Christmas” to represent a voice within one’s subconscious trying to communicate with the conscious mind – – again appears. “Heaven Sent” brings the symbol full circle, with the chalkboards now recalling Clara’s career in education.

Even the episode’s cinematography contains symbolism. Note how the Doctor’s face fades away and is replaced by a skull. This is called a “match cut,” and it is a way for filmmakers to subtly hint that the two things are connected, before revealing this key aspect of the plot. Another special technique can be seen as the Doctor first encounters the wall of adamantium azbantium. The Doctor assumes that the glow behind the wall is his TARDIS, and that he is “one confession away” from his freedom. As the Doctor realizes the true meaning of the “bird” clue, the camera’s focus is “pulled,” meaning it zooms in on the Doctor, while simultaneously showing more of the wall behind him. The effect makes the Doctor’s revelation feel both monumental, yet deeply personal. “I can’t keep doing this!” the Doctor cries, as he realizes what he must do. “Can’t I just lose? Just this once?”

Moffat builds upon this cinematic technique, within his script. The Doctor’s statement that he “can remember it all, every time” doesn’t refer to the repeated lives he must live in order to amass the time necessary to punch his way through the handwavium azbantium wall, but that each successive copy will “remember it all, every time,” because, to each successive “Doctor,” Clara’s death will have occurred only minutes prior. “Whatever I do, you still won’t be there,” the Doctor says, in perhaps the episode’s second saddest moment.* The scene recalls Series 7’s “Hide,” where a melancholic Clara opined that the time-traveling Eleventh Doctor would see her finite life as small and forgettable. “We’re all ghosts, to you. We must be nothing,” she said, yet, in “Heaven Sent” – – some 7,000 to two billion years later – – the Doctor is still reliving the anguish of her death. That’s not forgettable, that’s immortal.

This scene also references “The Time of the Doctor,” specifically Eleven’s regeneration where he (rather rudely) spent most of the time reminiscing about previous companion Amy Pond rather than saying goodbye to the current companion who had just saved his life. This homage mirrors that iconic image and serves to bookend Clara’s tenure with the Twelfth Doctor.

“Doctor, you are not the only person who ever lost someone,” says the impossible girl who, at this time, last series, held hostage all of the TARDIS keys in order to force the Doctor to save the deceased Danny Pink. This makes Clara herself one of the most poignant symbols in “Heaven Sent.” For two series, Clara’s story arc has measured her growth by how closely she has come to resemble the Doctor; here, the roles are reversed and Twelve must learn from her, giving Clara one last chance to be “the Doctor.”