Mark Gatiss: Playing to His Strengths

Guest contributor Levi E. Cohen-Kreshin on New Who’s more divisive writer.

Introduction

Mark Gatiss is one of the most prolific writers in New Who, having written the most episodes of the show other than the executive producer/lead writers. However, his six offerings to the show have all received fairly mixed reviews, and beyond the performances within an episode, the first thing that gets the blame is the script. I personally believe that Gatiss’ most recent episodes, Cold War and The Crimson Horror, have been his two strongest to date. I’ll explain why, because I think that Mark Gatiss really played to his strengths while writing these episodes. If he keeps wanting to succeed with his scripts, he should emphasize those strengths and stick to what he’s good at.

Period Settings

One thing that is undisputable about Gatiss’ episodes is that they really excel in setting the mood, especially in historical locations. All but one of his scripts take place in the past: Cardiff 1869, London during World War II and 1953, one on a 1983 Soviet submarine, and the last in Yorkshire in 1893. The script may falter, but the places themselves are richly detailed. Most recently, The Crimson Horror effortlessly transports the viewer from their televisions into the 19th century, and Gatiss enriches it with extra details about the time period that make it seem that much more realized. Optograms, for example, were a well-known belief in the 19th century. They were so widely believed in that the police photographed the eyes of murder victims in case it was true. The preaching of the coming apocalypse, the usage of a blind person as a curiosity: like it or not, the episode was fun to look at and fun to be immersed in.

One thing that is undisputable about Gatiss’ episodes is that they really excel in setting the mood, especially in historical locations. All but one of his scripts take place in the past: Cardiff 1869, London during World War II and 1953, one on a 1983 Soviet submarine, and the last in Yorkshire in 1893. The script may falter, but the places themselves are richly detailed. Most recently, The Crimson Horror effortlessly transports the viewer from their televisions into the 19th century, and Gatiss enriches it with extra details about the time period that make it seem that much more realized. Optograms, for example, were a well-known belief in the 19th century. They were so widely believed in that the police photographed the eyes of murder victims in case it was true. The preaching of the coming apocalypse, the usage of a blind person as a curiosity: like it or not, the episode was fun to look at and fun to be immersed in.

Gatiss knows exactly where and how to emphasize the setting: in Victory of the Daleks, not his best, yet not his worst outing, the Blitz-era London vibe is eagerly proven to the viewer, and then slides into the background in order to make way for the plot. Cold War didn’t seem to use the Cold War era as much as it could have until the very end, where the ending of the episode hinges on a nuclear missile launch, a very prevalent topic during the time period. The best way to see the impact the setting had on the episode is to imagine it set in the modern day, or without the flavour that the setting brought. Cold War becomes a base-under-siege story like any other; The Crimson Horror transforms into a pedestrian tale about a crazy old lady and her alien partner in crime. The setting is integral in Gatiss stories.

The lack of a historical “anchor” is extremely noticeable in the much-maligned Night Terrors, which excelled in creepiness but was without any interesting or original flair. To our disappointment we found ourselves in another council estate, with Eastenders-like drama (“But she can’t have kids!”) infused with a more typical alien tale. Gatiss is obviously uncomfortable writing a story that lacks an interesting setting to back it up, which leaves the script dry and boring until they actually enter a Victorian-style dollhouse. Gatiss has fun writing a historical script, and that translates to his work; I find Night Terrors difficult to watch because the writer’s enjoyment of his own script doesn’t carry over to me.

Horror

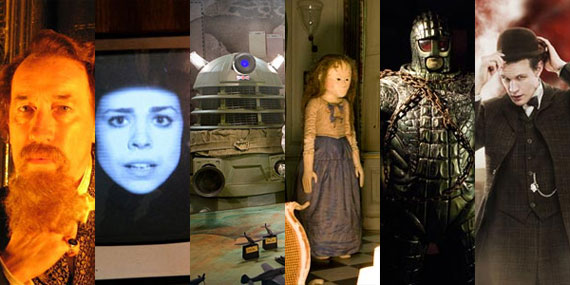

Gatiss’ vast knowledge of and deep passion for the horror genre shows in nearly all of his work (he has also, might I add, narrated several documentaries on the subject for the BBC). It’s prevalent in all of his work, even one of his “lighter” outings: The Idiot’s Lantern, a jaunty trip to the 50s, has the enemy suck the faces off of its innocent victims through their television screens. Although the episode the concept was in was lackluster, it was still a terrifying concept, and seeing Rose with her face wiped clean was quite scary. This is an example of “body horror”, which is exactly what it says on the tin. Time and time again Gatiss uses this kind of physical terror to great effect: the doll transformation in Night Terrors, Bracewell turning out to be a delusional robot in Victory, the Crimson Horror in The Crimson Horror, zombies in The Unquiet Dead… the list goes on.

Gatiss’ vast knowledge of and deep passion for the horror genre shows in nearly all of his work (he has also, might I add, narrated several documentaries on the subject for the BBC). It’s prevalent in all of his work, even one of his “lighter” outings: The Idiot’s Lantern, a jaunty trip to the 50s, has the enemy suck the faces off of its innocent victims through their television screens. Although the episode the concept was in was lackluster, it was still a terrifying concept, and seeing Rose with her face wiped clean was quite scary. This is an example of “body horror”, which is exactly what it says on the tin. Time and time again Gatiss uses this kind of physical terror to great effect: the doll transformation in Night Terrors, Bracewell turning out to be a delusional robot in Victory, the Crimson Horror in The Crimson Horror, zombies in The Unquiet Dead… the list goes on.

Body horror aside, Gatiss knows how to use suspense to build up an episode. Night Terrors sucks the council estate residents into the dollhouse, Cold War frees an Ice Warrior on a Russian submarine, and The Crimson Horror builds a peculiar tension with the revelation of Mr Sweet. Gatiss also used “jump scares” to good effect, like Ada’s ‘monster’ or the Ice Warrior grabbing people from above. The suspense and fear of the unknown inherent in the genre are also prevalent, be it the abilities of an Ice Warrior free of its armor, the mystery of the sinister Mr Sweet, or the slow, sing-song approach of the peg dolls. Each writer on Doctor Who is good at something; if they weren’t, they probably wouldn’t be writing for the show. Gatiss’ greatest asset is his ability to write horror unlike anybody else.

Character Development

This, I believe, is among Mark Gatiss’ strongest and weakest talent, as he is exceptional at creating guest characters but has trouble with the leads. Let’s take his most recent episode, The Crimson Horror. In my opinion, Ada and Winifred Gillyflower are among the two finest side characters the show’s had in recent memory. Ada is well-developed, sympathetic, and a very unique type of character, not only because of her blindness but because of her connection to the Doctor.

This, I believe, is among Mark Gatiss’ strongest and weakest talent, as he is exceptional at creating guest characters but has trouble with the leads. Let’s take his most recent episode, The Crimson Horror. In my opinion, Ada and Winifred Gillyflower are among the two finest side characters the show’s had in recent memory. Ada is well-developed, sympathetic, and a very unique type of character, not only because of her blindness but because of her connection to the Doctor.

Mrs. Gillyflower, on the other hand, is a vicious, insane woman under the influence of a prehistoric creature. Gatiss brings a bevy of secondary characters to the screen with every episode, be it the dysfunctional family of The Idiot’s Lantern or the struggling parents in Night Terrors. Each character is developed enough to be sympathetic or not, with some touching moments scattered throughout: Gwyneth’s death, Alex’s frustration at his inability to help George, or the moment when Tommy Connolly decides to try and reconnect with his father. All of these moments make Gatiss’ created characters seem real.

On the flipside, his characterization of the leads seems to vary. As many have noted, Cold War could have gotten rid of Clara entirely and not have the plot change (some minor tweaks would have to be made, but not much other than that), and The Crimson Horror similarly put the Impossible Girl on a backburner in order to make room for the Paternoster Gang. Gatiss’ scripts seem to work better on the companion-lite scale, but he always seems to reintroduce the character halfway into the episode for no reason at all.

Conclusion

To sum up Gatiss’ strengths, they are: a good setting, a good dose of scares, and a small supporting cast of interesting, believable characters. Hopefully, Moffat will have realized that Gatiss’ comfort zone of period pieces is where he really shines, and keeps him confined to that. What Gatiss should focus on is doing a complete companion-lite episode so he’s free from the confines of having to write an already fleshed-out character. Gatiss is a wonderful writer; he just needs to combine the right elements.